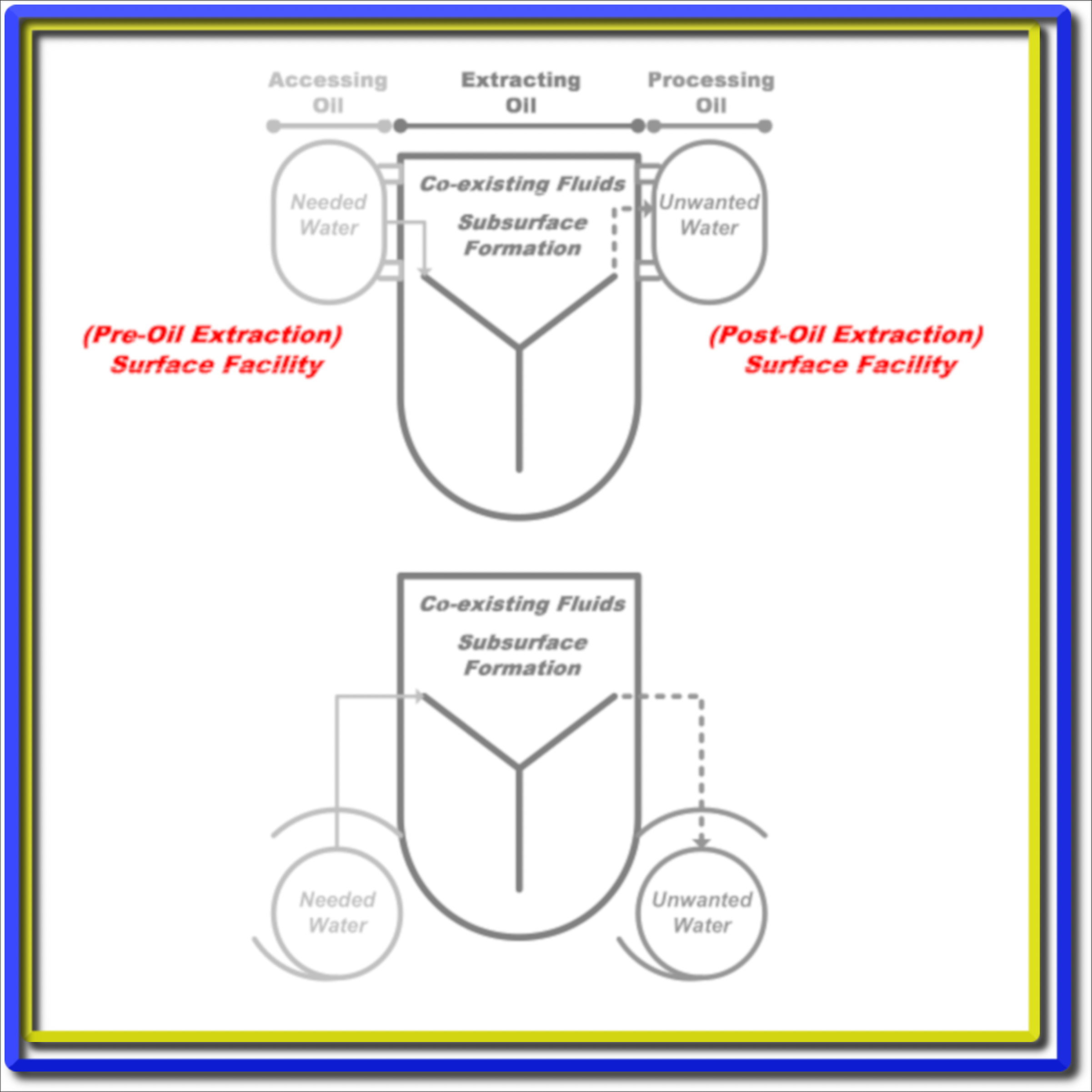

One “handle” (or one “wheel”) represents the needed water to access oil, and the other “handle” (or the other ‘wheel”) represents the unwanted excess water to be separated from wet oil. In order to hold the “pot” (or “bike”) steady, both handles must be grasped. It should be clear then that the term “oil recovery’’, regardless of its different labels, means at least an economic operation in which the value of the recovered oil exceeds its actual total production cost.

The total production cost comprises the cost of injecting water at a surface facility to access oil, the cost of separating water from the produced wet oil at another surface facility (a wet oil gathering center), and the cost of maintaining the entire elements involved in the oil recovery operation from injecting water through the oil-bearing formation to separating water from the produced wet oil, including deferred oil production.

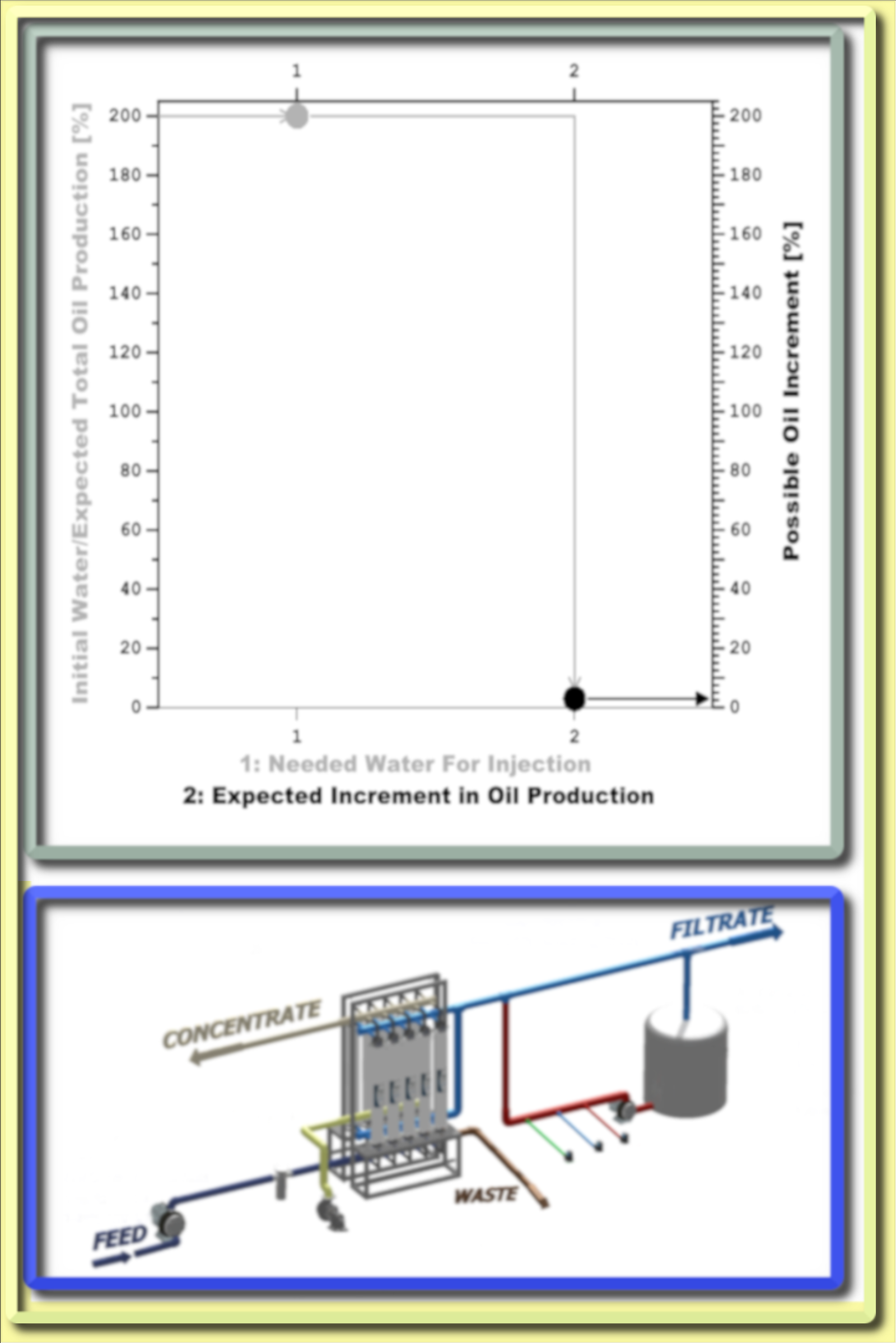

Almost in any blind water injection operation, the interfacial tension between the displacing fluid (water) and the displaced fluid (oil) may be reduced from a characteristic value of about 50 mN/m to values in the order of 1-10 mN/m; by which the increment in oil production may be in the order of 2-5%; and on which the required amount of water for injection starts from as low as twice (the middle figure on the left side) to as high as 10-times the amount of expected total oil production. It is quite obvious that an increase in the needed water supply by at least 200% of total fluids will potentially on average increase oil production by 3%; thereby dwarfing any potential oil increment on a volume basis.

Yet, almost always at the start of any water injection operation, water from an essentially free source is used with minimal pre-treatment, regardless of its chemistry contrasts with formation water and/or the formation itself, provided that the injectivity is not presumably affected by its content of total suspended solids. This is the very “usual practice”; it is rarely the case to provide proper treatment for the needed water from the start.

The silent ramifications of injecting water after such pre-treatment often incur huge deferred expenditures; which does not result in a sustainable oil recovery, but it could provide a short-lived oil production boost on the expense of frequent operation failures. For a production entity, such expenses come out of profits because every service contract dollar means one less dollar the entity has to earn, or a loss the entity has to write off.

What if it is worse than the “usual practice”? That is when the starting capital cost of a simple pre-treatment system is skyrocketed from the start before even allowances are made for the rather high costs of maintaining oil wells and expanding wet oil gathering centers due to water injection. What if a so-called proven service provider has been proven to be an outrageously expensive? For whom does this fail (loosing profits) and for whom does this work (harvesting profits)?

When and where such a pre-treatment of source water is perceived as a solution in oil-fields and/or in other applications but at extreme capital and operating costs, DESUL alternatively presents very economic reasons to build (and operate) cost effective and compact filtration and/or separation systems as well as standalone MF, UF, NF and/or RO systems.